Hamilton’s Blueprint: Building American Sovereignty from Paterson to 2025

Nationalists must examine the realities of our political situation and seek to innovate and shape our nation with the goal to procure her earthly and heavenly good through economic independence and prosperity.

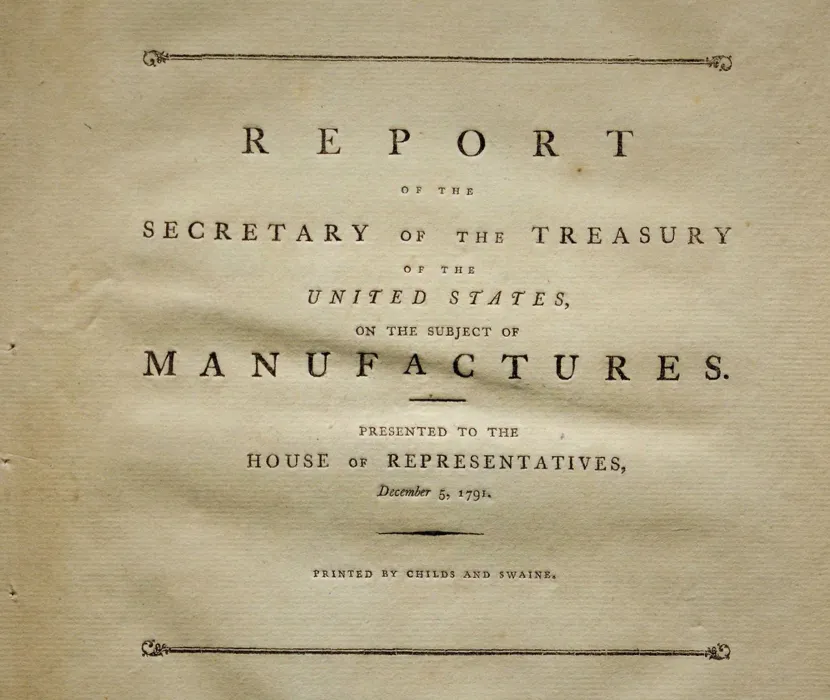

Setting the Stage with the 1791 Report on Manufactures

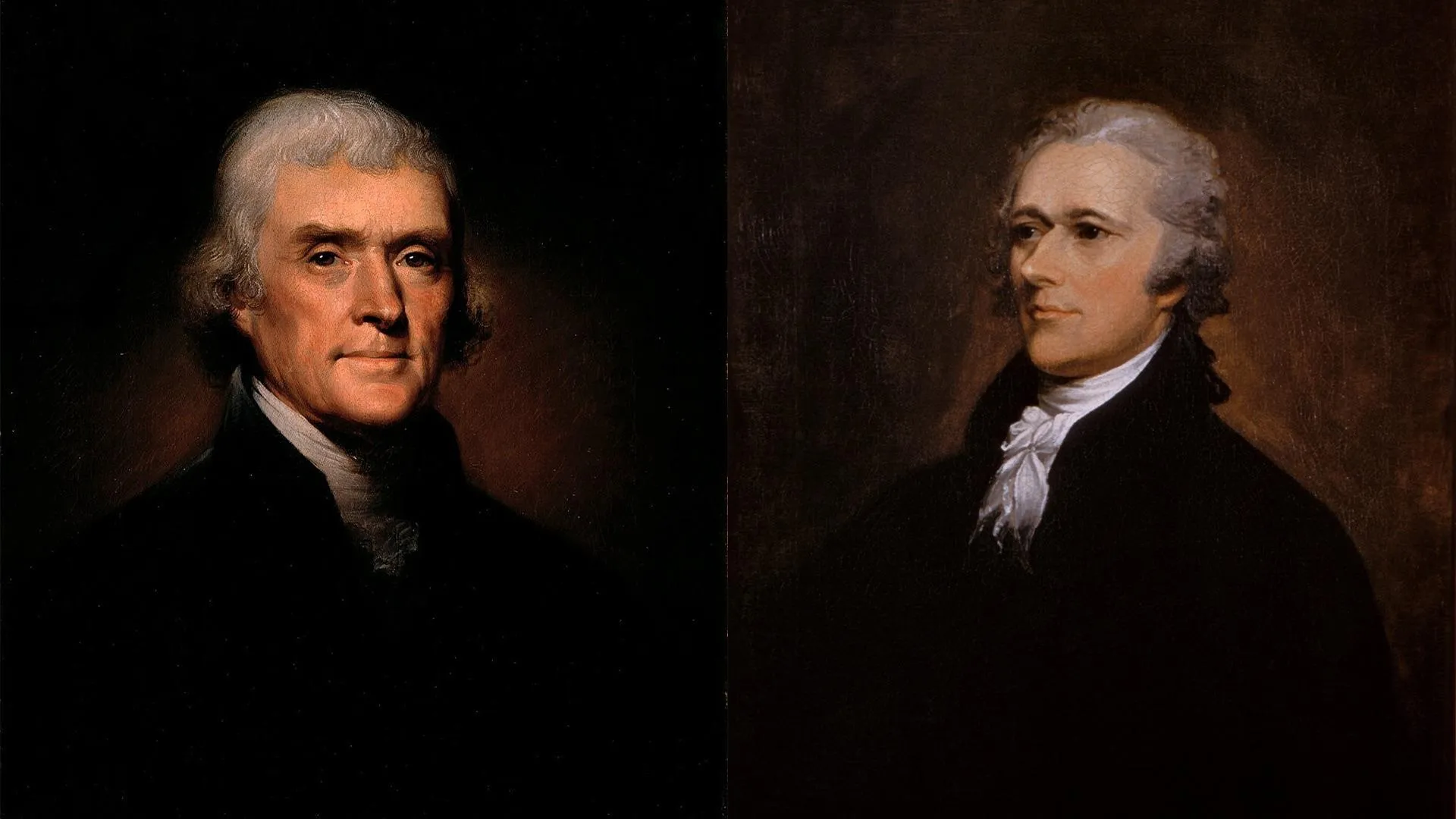

Soon after the adoption of the Constitution in 1789, our fledgling American nation was facing big economic challenges. Global power Great Britain, still reeling from its defeat in the Revolutionary War, would soon challenge the United States again in the War of 1812. With another war on the horizon, America had a desperate need to create a national economy and develop its industry in order to become a self-sustaining nation. The political debates at the time were raging between the Hamiltonian Federalists and the Jeffersonian Democratic-Republicans, who had differing visions for the economic direction of the nation. The Hamiltonians sought to industrialize through the power of a centralized executive while the Jeffersonians wanted a decentralized slave-based agrarian system.

Understanding the needs of the nation, President George Washington requested that his Secretary of the Treasury and right-hand man during the war, Alexander Hamilton, create an economic and financial plan for the new nation. His earlier reports on public credit and a national bank had laid the groundwork for stabilizing the U.S. economy. The 1791 Report on Manufactures became his third major economic proposal, and his magnum opus, focused on industrial policy. In his report, Hamilton rightly analyzed the precarious nature of America’s political and economic situation. He makes three general assertions. First, he says:

Not only the wealth; but the independence and security of a Country, appear to be materially connected with the prosperity of manufactures. Every nation, with a view to those great objects, ought to endeavour to possess within itself all the essentials of national supply.

In essence, Hamilton argues that domestic manufacturing ensures self-sufficiency and strengthens national security, reducing reliance on foreign powers.

Second, he observes:

Not only wealth, but the independence and security of a country, appear to be materially connected with the prosperity of manufactures. Every nation, with a view to those great objects, ought to endeavor to possess within itself all the essentials of national supply. These comprise the means of subsistence, habitation, clothing, and defense.

The possession of these is necessary to the perfection of the body politic; to the safety as well as to the welfare of society; the want of either is the want of an important Organ of political life and Motion; and in the various crises which await a state, it must severely feel the effects of any such deficiency. [emphasis added]

After seeing the Continental Army nearly crippled by the lack of supplies during the Revolutionary War, Hamilton viewed manufacturing as a bulwark against such vulnerabilities, as it would ensure the nation could withstand future conflicts without relying on foreign powers.

Hamilton’s third and often misrepresented critical point was that encouraging manufacturing was in the best interests of all parts of the Union: North, South, East, and West alike. This mantle was carried on seventy years later by men like Henry Carey, who argued in his book The Harmony of Interests that protectionism seeks the mutual interest of the manufacturer and agriculturalist and that this economic system would bind all men together toward a national goal.

The Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures

As Hamilton crafted his Report on Manufactures, he began to put his ideas into action through the creation of the Society for Establishing Useful Manufactures (SUM). Paterson, New Jersey was his location of choice, as the site was home to the 77-foot-high Passaic Falls, one of the largest waterfalls east of the Mississippi. His vision was to create an industrial city using hydroelectric power generated by the Falls. Hamilton knew that if he could prove his industrial policy to be fruitful in Paterson, then it could spur industrial development on a national scale.

Hamilton wrote in a prospectus for the SUM, published in August, 1791:

The establishment of Manufactures in the United States when maturely considered will be found to be of the highest importance to their prosperity. It is an almost self-evident proposition that that community which can most completely supply its own wants is in a state of the highest political perfection. And both theory and experience conspire to prove that a nation (unless from a very peculiar coincidence of circumstances) cannot possess much active wealth but as the result of extensive manufactures.

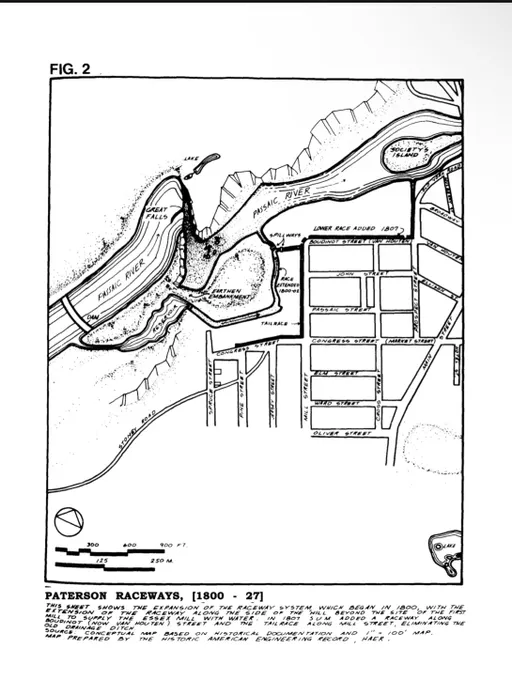

To bring his vision to life, Alexander Hamilton turned to some of the most capable minds of his era, enlisting Pierre Charles L’Enfant, the celebrated French-born engineer and architect, to design the innovative raceway system that would harness the power of the Great Falls of the Passaic River to run the mills in the city below. His design was ambitious: a three-tiered system of canals that would channel water from above the falls, through a series of controlled gates, and into the mills below, ensuring a steady and reliable energy supply for industrial production. L’Enfant’s engineering plan was not without challenges—rocky terrain, unpredictable river flows, and limited technology made the construction difficult, and his meticulous attention to detail often clashed with the practical demands of the project’s timeline and budget. By 1794, however, the raceway system was operational, a testament to L’Enfant’s vision and Hamilton’s determination to see the project through.

Another key player in the success of SUM was Peter Colt, a Revolutionary War veteran and experienced administrator. Colt, who served as the society’s first superintendent, oversaw the practical implementation of the raceway system and managed SUM’s early operations. He brought a pragmatic approach to the endeavor, ensuring that L’Enfant’s designs were executed efficiently despite financial constraints and logistical hurdles. Colt’s role extended beyond engineering—he was instrumental in securing funding, negotiating land leases, and attracting manufacturers to set up mills in Paterson. His family connections also played a significant role: his son, Roswell Lyman Colt, later became a key figure in SUM’s leadership, and through Roswell, the society supported Samuel Colt’s early ventures in Paterson, leading to the production of the iconic Colt revolver in 1836.

Together, L’Enfant’s visionary engineering and Colt’s steady leadership laid the foundation for Paterson’s transformation into an industrial powerhouse, proving that Hamilton’s ideas could be translated into a functioning system that powered cotton mills, textile factories, and eventually a diverse array of industries, from locomotives to silk production.

Developing the SUM was not without its financial challenges, so Hamilton sought the support of the state of New Jersey and its governor, William Paterson. After negotiations, the state agreed to charter the SUM as a corporation with the right to hold property, improve rivers, build canals, and raise funds through a lottery. It had the power to exercise eminent domain and would be exempt from taxes for ten years.

In Hamilton’s prospectus, he sought to assuage the two biggest objections toward manufactures: lack of capital, and the high price of labor. These challenges would be addressed through implementation of his financial system and the increased use of machinery. Hamilton wrote in response to the arguments about the lack of capital:

The last objection disappears in the eye of those who are aware how much may be done by a proper application of the public debt. Here is the resource which has been hitherto wanted; And while a direction of it to this object may be made a mean of public prosperity and an instrument of profit to adventurers in the enterprise, it, at the same time, affords a prospect of an enhancement of the value of the debt; by giving it a new and additional employment and utility.

Critics might decry “government overreach,” but Hamilton’s use of public debt and state support was a pragmatic response to the 1790s’ capital scarcity, enabling economic independence.

We will see in the next section that Hamilton’s ideas were vindicated in the success of Paterson, New Jersey, America’s first industrial city.

Building the Raceway: A Feat of Engineering

By 1794, the Great Falls Raceway and Power System was fully operational, marking a significant milestone in the United States’ journey toward economic independence. This engineering feat was no small accomplishment in the 1790s, a time when the young nation lacked advanced machinery and relied heavily on manual labor for construction. Workers blasted through basalt cliffs, constructed wooden dams, and dug canals by hand, overcoming harsh weather, flooding, and financial constraints to bring Hamilton’s dream to life.

The raceway powered cotton mills, including the “Old Yellow Mill,” which began spinning yarn and cloth, marking a key step in Hamilton’s plan to reduce reliance on British textiles.

Paterson’s Industrial Ascendancy: From Cotton to Silk City

Over the next decade, the SUM expanded the raceway system, adding more mills and increasing production capacity, which solidified Paterson’s role as a proving ground for Hamilton’s industrial vision. Paterson’s cotton mills supplied textiles that sustained the nation during the British blockades in the War of 1812, thus proving Hamilton’s vision. Over time, the city’s industries expanded to include silk, locomotives, and firearms.

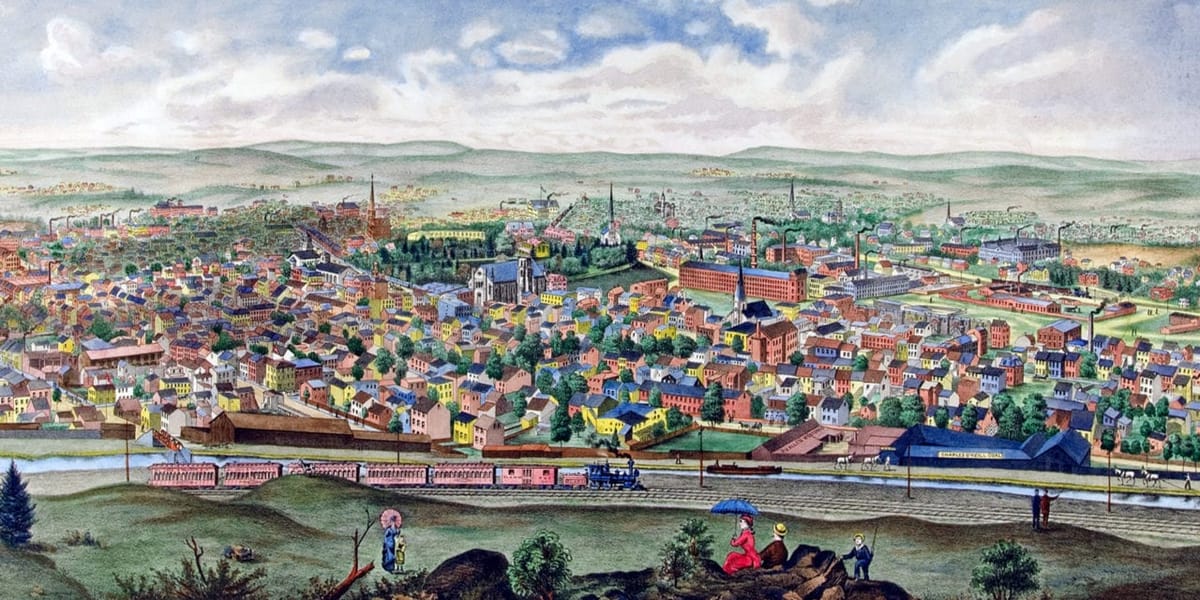

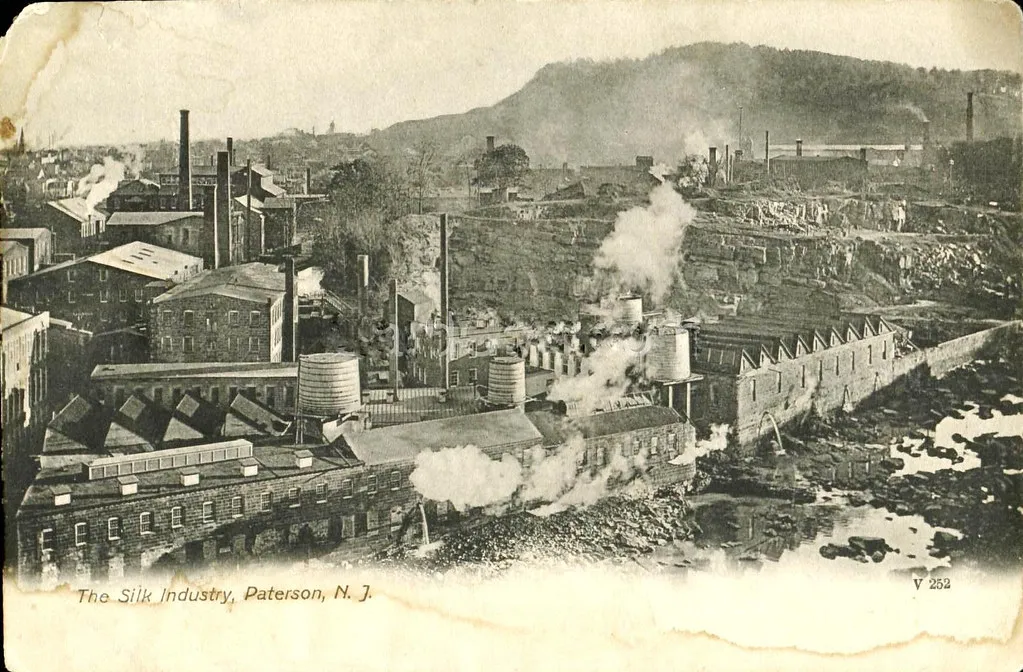

The success of the Great Falls Raceway laid the foundation for Paterson’s transformation into a major industrial hub, evolving far beyond its initial cotton mills to become a center of innovation and production by the 19th century. The raceway’s reliable water power attracted a diverse array of industries, each contributing to Paterson’s reputation as a cradle of American manufacturing. By 1815, the city boasted 13 water-powered cotton mills employing over 2,000 workers, a significant leap from its population of just 500 in the 1790s. This growth, spurred by SUM’s infrastructure, saw Paterson’s population swell to over 5,000 by 1820, reflecting its rapid emergence as an industrial powerhouse.

The city’s mills expanded into textile production beyond cotton, with a particular focus on silk by the late 1830s. Silk manufacturing took off after artisans, some of whom brought illegal copies of British mill designs, established operations in Paterson, leveraging the raceway’s power to run looms at scale. By the late 19th century, Paterson was producing silk fabrics in such quantities that it earned the moniker “Silk City,” supplying over half of the silk used in the United States and becoming a global leader in the industry. The Allied Textile Printers Complex, established in 1836, became a key player in this sector, weaving silk mosquito netting and other fine fabrics that were exported worldwide.

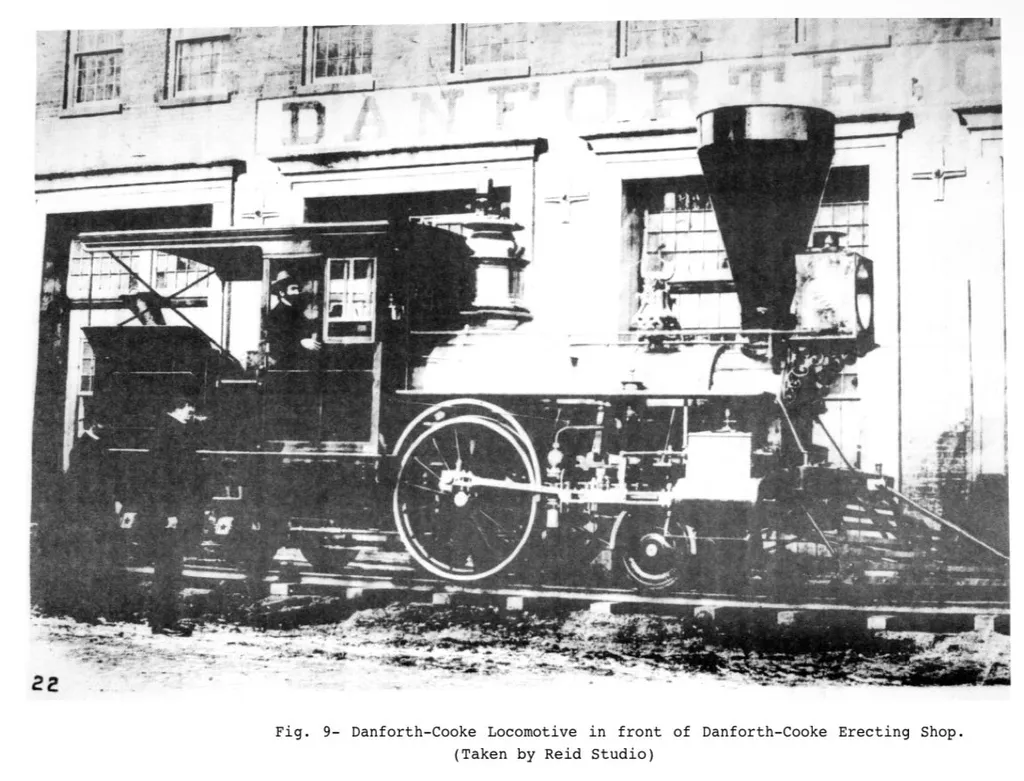

Beyond textiles, Paterson’s industrial output grew to include steam locomotives, with the Rogers Locomotive Works producing engines that powered America’s expanding railroads, such as the Danforth-Cooke locomotive, a marvel of 19th-century engineering. The city also became a center for firearms manufacturing, with the Colt Gun Mill—opened in 1836 by Samuel Colt, a descendant of Peter Colt—producing the first Colt revolver, a weapon that revolutionized military and civilian defense. By the early 20th century, Paterson’s factories were manufacturing aircraft engines, including those by Curtiss-Wright, which played a critical role in aviation advancements during and after World War I. The Holland submarine, an early prototype of modern naval technology, was also developed in Paterson, further showcasing the city as a hub of industrial innovation.

This diverse industrial output not only demonstrated the success of Hamilton’s vision but also highlighted the raceway’s enduring utility as a power source. The Great Falls Raceway enabled Paterson to produce goods that met Hamilton’s criteria for national supply—clothing (through textiles and silk), defense (through Colt revolvers and aircraft engines), and infrastructure (through locomotives)—while fostering economic growth that benefited the entire nation. By the turn of the 20th century, Paterson had become a symbol of what a government-supported industrial policy could achieve, proving that Hamilton’s ideas could indeed transform a nation’s economy and secure its place on the global stage.

Legacy of the “American System”

The success of Paterson was just the beginning of Hamilton’s broader influence, as his ideas gave rise to the “American System,” a framework that shaped the nation’s economic development for over a century.

Ultimately, Hamilton’s industrial policy came to life in the creation of Paterson, New Jersey, through an active role of the federal government in providing credit for economic growth. This showed that nationalists must take a proactive and innovative approach to governance and economics. His ideas were carried on by great statesmen and thinkers like Matthew Carey, Henry Carey, Friedrich List, Henry Clay, Abraham Lincoln, and eventually Donald Trump.

Hamilton himself had referenced a unique American System in Federalist No. 11:

Let Americans disdain to be the instruments of European greatness! Let the thirteen States, bound together in a strict and indissoluble Union, concur in erecting one great American system, superior to the control of all transatlantic force or influence, and able to dictate the terms of the connection between the old and the new world!” [emphasis added].

The American System developed into a three-legged stool comprising the National Bank (a national credit system), a system of protection (tariffs, support for labor, and crucial industry), and internal improvements (infrastructure such as railroads or canals).

Free-traders and small-government libertarians argue that protectionism distorts markets and raises consumer prices, but Hamilton’s American System demonstrated that strategic government intervention could foster industrial growth and elevate living standards, as seen in Paterson’s thriving economy. According to economic historian Robert E. Wright, it was under the protectionist policies of the 1870s–1910s (the height of America’s industrial takeoff) that American wages were the highest in the world, reflecting unprecedented prosperity (The Poverty of Slavery, 2017).

Hamilton’s Vision in the Modern Era

Hamilton’s 1791 Report on Manufactures, which powered Paterson’s Great Falls Raceway, offers a timeless model for economic independence in 2025. The COVID-19 pandemic, for example, revealed America’s reliance on global supply chains. With 70 percent of personal protective equipment coming from China and semiconductor shortages disrupting industries, the import dependence Hamilton sought to end was on display. His vision inspired modern policies like the CHIPS and Science Act, which reshore critical manufacturing to safeguard national security. Donald Trump’s proposal of “Freedom Cities” outlined this vision in a 2024 campaign video. Evoking Hamiltonian innovation, Trump called for new infrastructure and technologies like flying vehicles to reignite the American Dream.

Preserved as a National Historical Park, Paterson stands as a testament to Hamilton’s foresight, proving that government-supported industry can transform a nation. Today, as geopolitical tensions over semiconductors and pharmaceuticals loom, Nationalists must heed Hamilton’s lesson: true sovereignty demands action—building resilient systems, not just theorizing—to secure America’s future and power, a principle as vital now as in 1791. Nationalists must examine the realities of our political situation and seek to innovate and shape our nation with the goal to procure her earthly and heavenly good through economic independence and prosperity.