Thanksgiving: Statecraft for a Christian Nation

The Supreme Sovereign of Nations establishes the state, and we mark the calendar accordingly.

I. Bells, Drums, and A Day Set Apart

The morning is bright and sharp. Bells ring; a drum rolls.

The proclamation is read: let us set this day apart for public thanksgiving and prayer.

Work pauses. Pews fill.

From city pulpits to country meetinghouses, the same theme: the Almighty God has preserved the Nation; rulers must set the example of gratitude and repentance. President Washington observes the day at St. Paul’s. Governor Strong urges churches and households to assemble, “to humble ourselves before Him, as a People, that He would forgive our sins, and be merciful to us, as He ever has been to those that love His name.”

A republic orders its gratitude liturgically: one people, many blessings, consecrating a day before Almighty God.

Where Jefferson and the Anti-Federalists demurred, Federalists spoke aloud the older Anglo-Protestant assumption that Christianity and virtue are the foundation of political prosperity, and so they set the nation’s repentance and thanksgiving to a public rhythm, the tolling bell answering the roll of the drum. They held that the Supreme Sovereign of Nations establishes the state, and they marked the calendar accordingly.

Modern Thanksgiving has become primarily focused on food, family, and football, but our nation's tradition points to something higher. Let these proclamations tutor us again. Before the turkey and the game, gather your people, read Scripture, sing a psalm, pray for our rulers and for mercy. If the early republic could mark its gratitude in public worship, Christians today can begin to reclaim the heart of it in our homes and churches: through repentance and thanksgiving to the God who rules the nations.

II. From Plymouth to the Early Republic: The Making of a Thanksgiving Tradition

The consecration of a day to give thanks to the Almighty God for the fall harvest is a tradition that traces back centuries to European Christendom. In the colonies, the 'First Thanksgiving' was in the Plymouth Colony shortly after the first successful harvest of 1621 after the devastating winter of 1620-1621 that killed half of the Pilgrim colonists. Edward Winslow wrote in Mourt's Relation:

"Our corn turned out well and, God be praised, we had a good harvest of Indian corn. After we had brought in the harvest, our governor sent four men out to hunt fowl so that we might, in a special way, rejoice together after gathering the fruits of our labor. We entertained and feasted them [Indians] for three days, and they went out and killed five deer, which they brought to the plantation and gave to our governor, the captain, and others. And although it is not always so plentiful with us as it was at that time, yet by the goodness of God we are so far from want that we often wish you could share in our plenty." (Language modernized) [1]

This tradition of giving thanks to God for his blessing and gathering together to celebrate that blessing carried on throughout the colonial times, during the Revolutionary War, and into America's infancy.[2] Federalist leaders took that inherited habit of public gratitude and translated custom into principle, and principle into policy.

Federalists believed in this simple chain: Christianity yielded virtue and morality, and these, in turn, yielded social stability. Washington notes this in his Farewell Address: "Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports." Vital to the health of a nation is the blood of Christianity running through its veins. If you drain that blood, the nation will die. Adams made the same point in his most famous quote, "Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other." In this Federalist frame, magistrates who encourage public religion are doing their duty to their people, protecting the very core of the nation.

Thanksgiving and fast-day proclamations functioned as a civic liturgy; the magistrate set the day and instructed its purpose; churches and clergy led the worship; households joined the rite. This rightly ordered the nation toward God, repenting of national sins and giving thanks for the blessings bestowed by the Lord.

Federalists drew on not only colonial tradition but also that of state-level proclamations like Governor Jonathan Trumbull's proclamation appointing Thursday, Sept. 19, 1776 as a Day of Fasting and Prayer, calling the populace to humble themselves before God in the midst of war. This was a clear state-level template for later Federalist usage: civil scheduling, church assembly, reverential tone.

"I have therefore, by and with the Advice of the Council, thought fit to appoint, and do hereby appoint Thursday the nineteenth Day of September, to be observed as a Day of Fasting and Prayer throughout this State; hereby exhorting Ministers and People of all Denominations, to humble themselves before God, confessing their Sins, and intreating His divine Grace, Favor and Blessing. Particularly, to confess and lament their having gone far from God, forgetting the Errand of their Fathers into this Land, neglecting and abusing the inestimable Privileges of the Gospel, and trifling with the Liberties wherewith Christ hath made us free."[3]

On September 25th, 1789, Presbyterian Federalist Elias Boudinot sought to enshrine this practice into the Chief Magistrate by proposing a resolution in Congress to create a joint committee to "wait on the President of the United States, to request that he would recommend to the people a day of public prayer and thanksgiving.”[4] Boudinot was drawing on the tradition established by the Continental Congress during the Revolutionary War, when it proclaimed days of national thanksgiving, as well as many state governors who issued their own proclamations.

While his efforts led to the passage of the resolution, it was not without opposition led by Jefferson's Anti-Federalists on two primary grounds. Anti-Federalist and South Carolinian Aedanus Burke claimed it was too "European." He argued essentially that it emulated what he interpreted to be an empty tradition of both sides of a war singing Te Deum, an ancient Christian hymn of praise. If both sides were thanking God in victory and defeat, then the rite becomes hollow pageantry, but on a Christian doctrine of providence Burke’s conclusion does not follow. Rituals are not innately empty, but, when rightly ordered, can bring all people to acknowledge God's justice in their success or defeat, confessing their failures, and giving thanks for chastening and mercy alike. The problem is not civil days of prayer and praise as such, but rather dishonest rituals; a well-ordered national Thanksgiving answers Burke’s worry by making public worship the place where a people names both its blessings and its judgments under God.[5]

The second notable objection came from another South Carolinian Anti-Federalist, Thomas Tudor Tucker, on the grounds of the separation of church and state. He argued it was not up to the federal power to opine on religious matters, but instead should be left to the states: “If a day of thanksgiving must take place, let it be done by the authority of the States.” Tucker also worried that any national thanksgiving proclamation would be an improper mingling of church and state, since, in his view, such a proclamation was essentially a religious act.[6]

This line of reasoning anticipates Thomas Jefferson’s later position. In an 1808 letter, Jefferson wrote:

“I consider the government of the US. as interdicted by the constitution from intermedling with religious institutions, their doctrines, discipline, or exercises. This results not only from the provision that no law shall be made respecting the establishment, or free exercise, of religion, but from that also which reserves to the states the powers not delegated to the US. Certainly no power to prescribe any religious exercise, or to assume authority in religious discipline, has been delegated to the general government.” [7]

But this objection fails if one begins from historic Christian political theology rather than late-modern liberal scruples. The chief magistrate is charged with the care of the commonwealth’s virtue and the promotion of true religion; it is not an “establishment of religion” for a civil ruler to call the people to give thanks to God for his blessing, but an exercise of his office as God's servant. Public acknowledgment of divine blessing without prescribing a particular denomination fits comfortably within the historic Protestant understanding of the magistrate’s duties, as well as Romans 13:4, which says about the magistrate, "he is the minister of God to thee for good."

Despite these repudiations of the resolution, it passed in Congress. Roger Sherman, one of the members of the newly formed committee, praised the resolution, saying, "a laudable one in itself." It was also "warranted by a number of precedents in the Bible," he said, "for instance the solemn thanksgivings and rejoicings which took place in the time of Solomon, after the building of the temple." They delivered the message to President Washington who responded declaring November 26th, 1789, to "be devoted by the People of these States to the service of that great and glorious Being, who is the beneficent Author of all the good that was, that is, or that will be." America's Christian Prince echoed the language of Revelation 1:4—"from him which is, and which was, and which is to come;" (KJV)—and the Gloria Patri—"as it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be," a historic Christian liturgy.

III. Statecraft by Prayer: Federalist Thanksgiving in Practice

With the frame in place, the proclamations read like statecraft by prayer. Here are a few of the clearest Federalist examples.

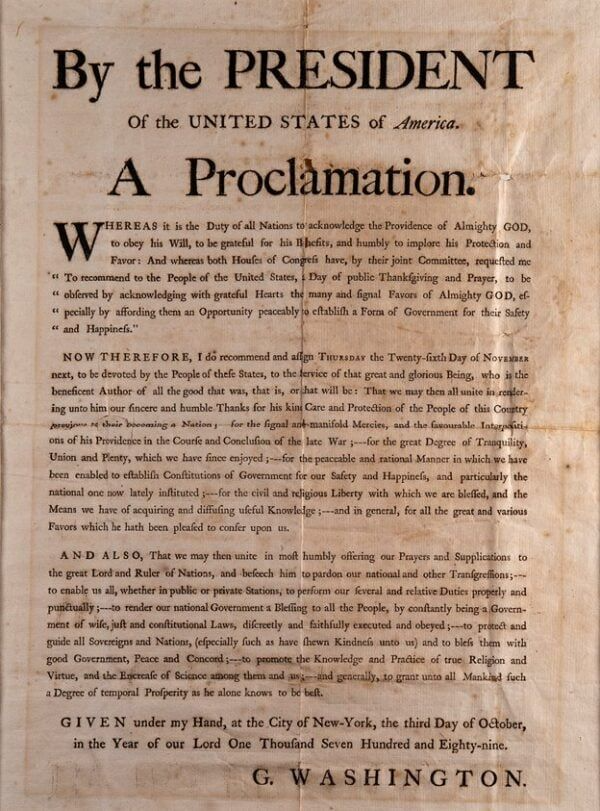

George Washington's first Proclamation was delivered October 3rd, 1789. His Proclamation starts with a recognition that "it is the duty of all Nations to acknowledge the providence of Almighty God, to obey his will, to be grateful for his benefits, and humbly implore his protection and favor." He then calls for the nation to give thanks for God's protection through the Revolution, "for his kind care and protection of the People of this Country previous to their becoming a Nation—for the signal and manifold mercies, and the favorable interpositions of his Providence which we experienced in the course and conclusion of the late war—for the great degree of tranquillity, union, and plenty, which we have since enjoyed." Washington ends the Proclamation with two strong statements, first humbly asking "the great Lord and Ruler of Nations and beseech him to pardon our national and other transgressions" and secondly asking God in his wisdom, "To promote the knowledge and practice of true religion and virtue, and the increase of science among them and us—and generally to grant unto all Mankind such a degree of temporal prosperity as he alone knows to be best."[8]

This was not a one-off for Washington, as he also made a proclamation in 1795 after "the recent confirmation of that tranquillity by the suppression of an insurrection which so wantonly threatened it," referencing the Whiskey Rebellion. He went on to state,

"In such a state of things it is, in an especial manner, our duty as a people, with devout reverence and affectionate gratitude, to acknowledge our many and great obligations to Almighty God and to implore him to continue and confirm the blessings we experience."[9]

Despite John Adam's quietly held Unitarian convictions, he felt the pressure to conform to his Christian Federalist Party traditions in his National Fast Proclamation in both 1798 and 1799. Following the footsteps of the Father of our Nation, he urged, "The safety and prosperity of nations ultimately and essentially depend on the protection and the blessing of Almighty God; and the national acknowledgment of this truth is not only an indispensable duty which the People owe to him."

He recommended the nation to abstain from work, gather with other Christians, and repent, saying this was,

"a day of Solemn Humiliation, Fasting and Prayer: That the Citizens of these States, abstaining on that Day from their customary Worldly Occupations, offer their devout Addresses to the Father of Mercies, agreeably to those forms or methods which they have severally adopted as the most suitable and becoming: That all Religious Congregations do, with the deepest Humility, acknowledge before God the manifold Sins and Transgressions with which we are justly chargeable as Individuals and as a Nation..."[10]

Many of the more theologically rich proclamations came from Caleb Strong, a Founding Father, Congregationalist, and Governor of Massachusetts. He offered many proclamations in his two stints as governor (1799-1807; 1812-1816). I will draw on two, one from each term.

In 1806, the Federalist Governor sought to bind his state together in this endeavor saying, "That the People of this State may be of one mind, and live in peace; and that all bitterness, and wrath, and clamour, may be put away from us, with all malice; and that we may speak every Man the truth to his neighbor." He wanted this day to be a means to sanctify his citizens toward their heavenly good saying, "That the Gospel may be attended with convincing evidence of its Divine authority, and with efficacy and success in reforming the lives and purifying the hearts of men." Strong also desired God's blessing on the state's industry, agriculture, and education saying, "That He would protect our Commerce, and prosper our Manufacturers and Fisheries; and that by His blessing on the instructions and government of our Colleges and Schools, the minds of our Youth may be enlightened and cultivated, and formed to habits of virtue, industry and subordination."[15]

In Caleb Strong's second term as governor in 1813, he declared in strong covenantal language,

"Therefore, with the advice and consent of the Council, I appoint THURSDAY, the eighth day of April next, to be observed by the people of this State as a day of public Fasting, Humiliation, and Prayer: and the several denominations of Christians are requested to assemble on that day, that we may unite in humble adoration of the Divine Being who retains not his anger forever, because he delights in mercy; and beseech Him that he would look from Heaven, his holy habitation, and bless this people and the land which he has given us: and that He would establish his Covenant between Him and us, and our children after us, for an everlasting Covenant."

Strong goes so far as to invoke the name of Jesus Christ to bring peace to the ends of the earth expressing, "That He would confound the devices of the enemies of His Church, so that their hands shall not perform their enterprise: That He would make wars to cease to the ends of the earth, and that all nations may know and be obedient to that grace and truth which came by Jesus Christ." Lastly Strong requests an extraordinary Sabbath day to honor the proclamation, "And the people of this State are requested to abstain from unnecessary labour and recreation on the said day."[16]

Caleb Strong, Governor of Massachusetts, with his Proclamation.

My personal favorite proclamation comes from John Jay's time as Governor of New York in 1795. In the wake of an epidemic that had plagued New York City, he rightly acknowledges God's Sovereignty starting the proclamation with, "Whereas the Great Creator and Preserver of the Universe is the Supreme Sovereign of Nations, and does, when and as he pleases, reward or punish them by temporal Blessings or Calamities, according as their National Conduct recommends them to his Favor and Beneficence, or excites his Displeasure and Indignation." Reminding his constituents of a Reformed emphasis on God's decree, he echoes Romans 9:15, "For He says to Moses, ’I will have mercy on whomever I will have mercy, and I will have compassion on whomever I will have compassion.’"

Jay goes on to lay the responsibility on the Magistrate to promote true religion, stating,

"Wherefore, and particularly on this occasion it appears to me to be the public duty of the People of this State collectively considered, to render unto him their sincere and humble Thanks for All these his great and unmerited Mercies and Blessings— And Also to offer up to him their fervent Petitions to continue to us his Protection and favor, to preserve to us the undisturbed Enjoyment of our Civil and Religious Rights and Privileges, and the valuable Life and usefulness of the President of the United States— To enable all our Rulers Councils and People to do the Duties incumbent on them respectively with Wisdom and fidelity— To promote the extension of true Religion, Virtue and Learning."

He finally ends by instructing the people and even the clergy to consecrate the day, and that it is required for God to bless the nation, echoing, "Blessed is the nation whose God is the Lord" (Psalm 33:12), by saying,

"But as the People of the State have constituted me their Chief Magistrate, and being perfectly convinced that National Prosperity depends, and ought to depend, on National Gratitude and Obedience to the Supreme Ruler of All Nations, I think it proper to recommend and therefore I do earnestly recommend to the Clergy and others my fellow Citizens throughout this State to set apart Thursday the twenty sixth day of November instant for the Purposes aforesaid and to observe it accordingly." [17]

IV. A Federalist Theology of Nationhood

Read together, these texts yield a compact Federalist theology of nationhood that I will outline in six brief points.

1. Providence & National Covenant (God as Ruler of Nations; national sins/blessings).

Federalists spoke of God as the active Ruler of Nations, seeing national events as blessings or curses with corporate meaning. They referred to God as "Providence," emphasizing his work in directing the nation. The republic, therefore, bore national responsibilities: gratitude in prosperity, repentance in calamity, and continued petition for God's favor. Proclamations taught Americans that harvests, safety from enemies, and prosperity required public acknowledgement rather than private sentiment alone.

2. Magistrate & True Religion (encouragement, not denominational-establishment).

In this vision, the magistrate is not establishing a church or administering the sacraments; he is encouraging Christianity as the source of vitality of the nation. Calling for a day set aside for worship, rest from work, and thanksgiving is aimed at promoting the earthly and heavenly good of its people. The magistrate is to make room for Christianity to flourish, empowering families and churches to publicly honor God.

3. Public Worship as Civic Liturgy (assemble in churches; abstain from work; family worship).

The Magistrate, through the means of the proclamations, structures the day: requesting the people to abstain from work, to assemble in churches, pray for their rulers, confess their sin, and render thanks. By aligning calendars across congregations and households, they create a shared civic rite that binds disparate regions into a collective people. Families carry the observance home with psalm-singing and prayer, extending the day’s worship beyond the sanctuary.

4. Promotion of the People's Piety (repentance of vices, Sabbath, charity, obedience to law).

The proclamations consistently call the people to the obedience of God: suppressing vice and immorality, honoring the extraordinary Sabbath day, practicing charity, and obeying just law. Clergy echo and expand these themes from the pulpit, translating national repentance into concrete habits. This affirms the Federalist chain of public Christianity leading to virtue and thus vitalizing your nation.

5. Union over Faction (gratitude/repentance to heal factionalism).

Federalists understood the importance of a united nation. This principle is a staple to the Federalist program, not only in the Proclamations, but is seen in many other places throughout American history as well. One such notable moment is Washington's Farewell address in which he urges the nation, "The name of American, which belongs to you in your national capacity, must always exalt the just pride of patriotism more than any appellation derived from local discriminations. With slight shades of difference, you have the same religion, manners, habits, and political principles." This is a running theme among Federalists and the Proclamations aimed to set aside factional differences and unite as one nation under God.

6. Economic/diplomatic blessings as theologically interpreted

Material success in all manner of industry, agriculture, and commerce is framed as gifts from God entrusted to the people and must be stewarded for the good of America. This trains the populace that when they have success in war, protection from calamities, and preservation as a nation, it is the duty of that nation to give thanks to God. Even Hamiltonian statecraft, such as treaty negotiations, public credit, and internal improvements fall under this theological frame as stemming from the Almighty God.

V. From Proclamation to Pulpit to People

Having examined the proclamations and their theology of nationhood, providence, and the magistrate, we can now ask: how did these convictions shape practical action? These proclamations were not just empty rituals; they led to sermons, charity, church attendance, and extraordinary Sabbath observance. The Magistrate was not just speaking piously; in effect, he scheduled repentance and thanks, creating a civic holy day that was to be observed by all.

a. Washington’s 1789 Thanksgiving as a case study

President Washington’s 1789 proclamation was published widely in newspapers, then forwarded to the governors with an explicit expectation that they announce and observe it in their states. On the day itself, he noted his attendance at St. Paul's Chapel, New York, “Being the day appointed for a thanksgiving I went to St. Pauls Chapel though it was most inclement and stormy—but few people at Church.”[11] This confirms the expectation to attend church as the result of the proclamation, and it also implies that a crowd would have been expected had there not been inclement weather. He also donated "provisions and beer" to prisoners confined for debt in the city.[12] Washington led by example, following his own words by setting aside the day for worship and performing his duty by properly caring for the distressed.

b. The sermon boom: proclamations as engines of print and preaching

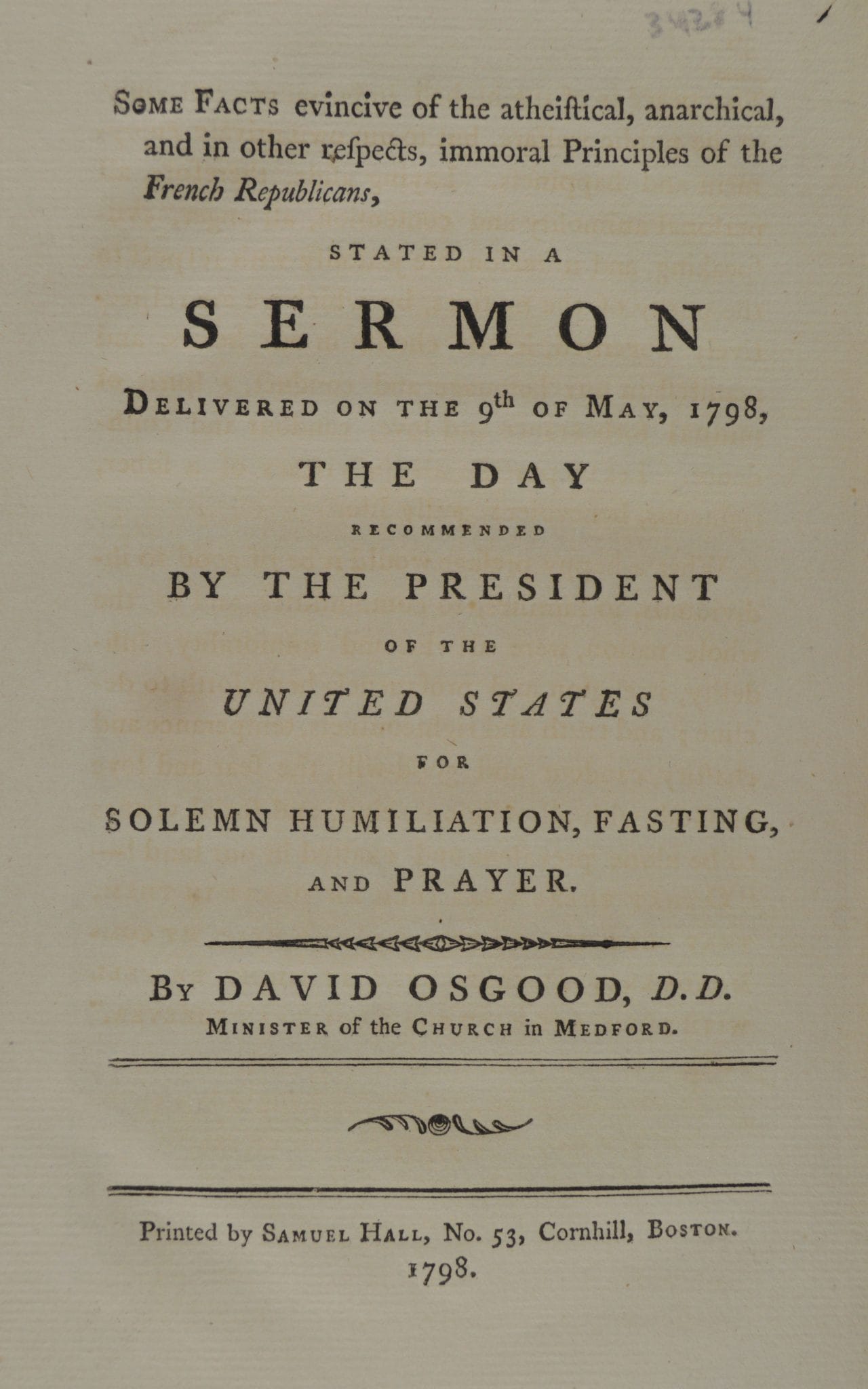

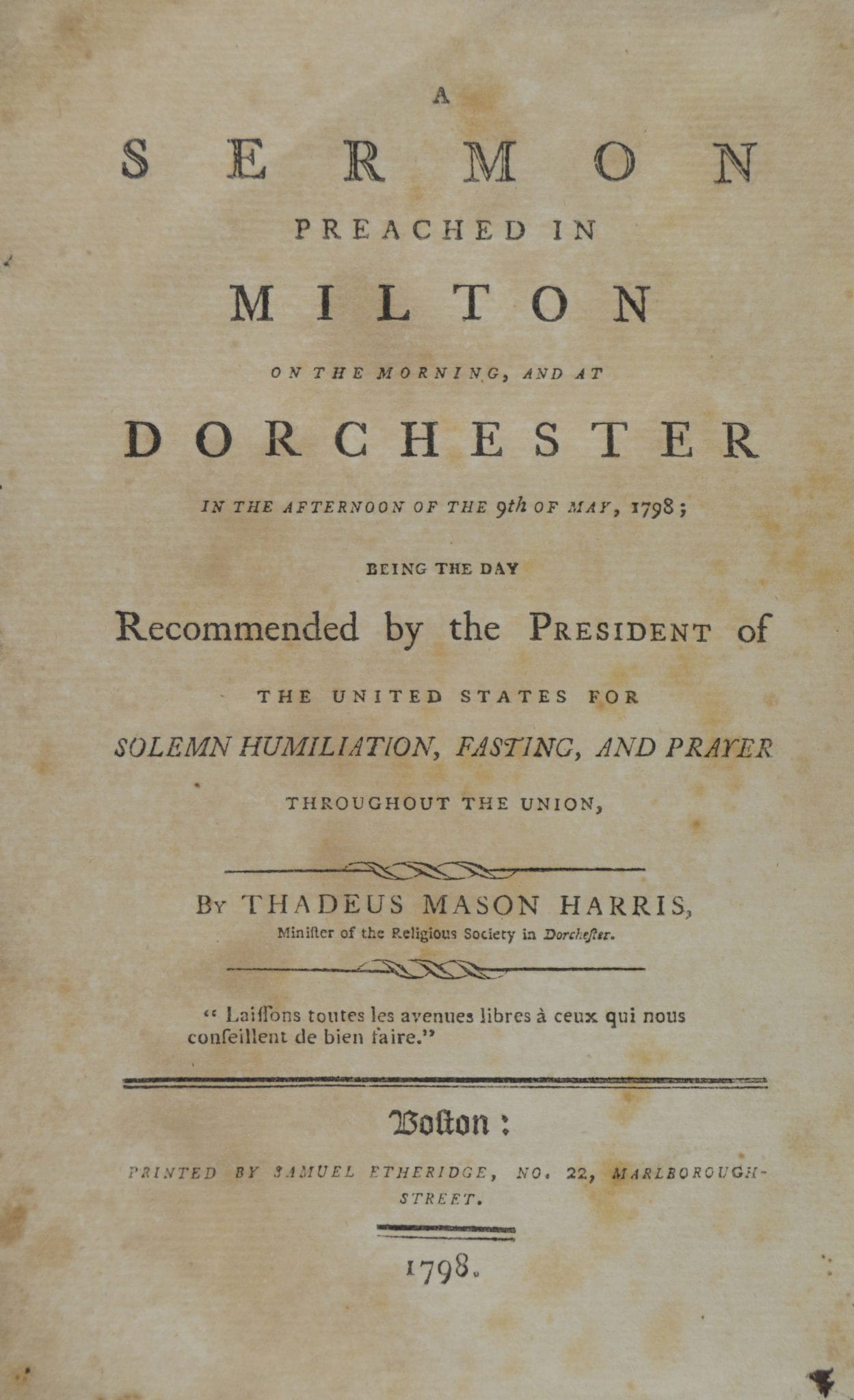

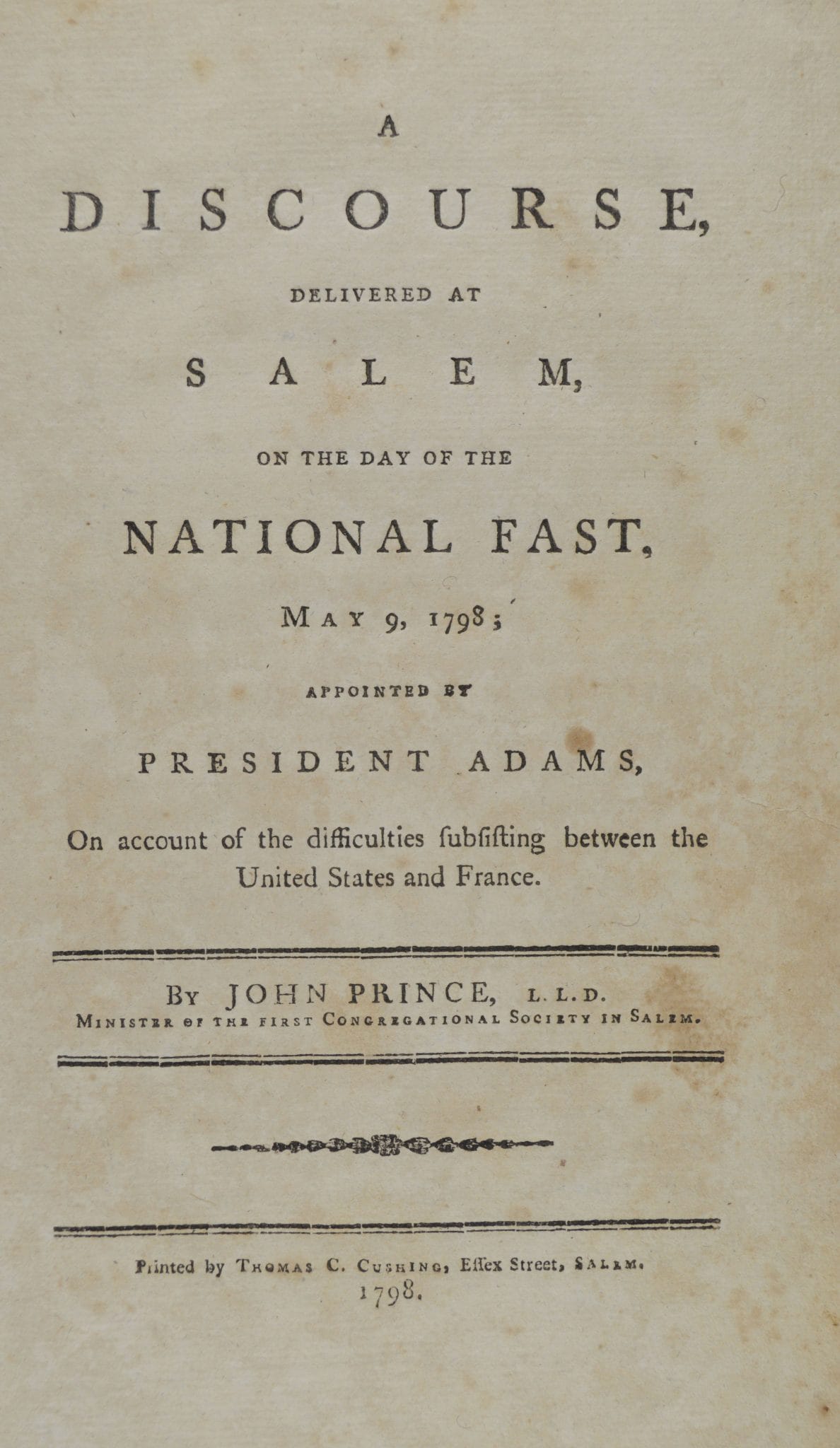

President Adams' proclamations led to an explosion of dated, proclamation-specific sermons. In March 23, 1798, his proclamation recommended May 9, 1798 as a national day of “solemn humiliation, fasting, and prayer,” connecting repentance to the French crisis and the preservation of American “civil and religious privileges.”

That one day generated a small library of sermons, many of which were printed and sold:

- Jeremy Belknap, Boston: A sermon, delivered on the 9th of May, 1798, the day of the national fast, recommended by the president of the United States llds.ling-phil.ox.ac.uk+1

- Jedidiah Morse, Boston/Charlestown: A sermon, delivered at the New North Church in Boston, in the morning, and in the afternoon at Charlestown, May 9th, 1798, being the day recommended by John Adams… for solemn humiliation, fasting and prayer. WorldCat+1

- Thaddeus Mason Harris, Milton & Dorchester: Sermon preached in Milton, and at Dorchester, on the morning and afternoon of the 9th of May, 1798; being the day recommended… for solemn humiliation, fasting and prayer Online Books Page

- Samuel Miller, New York: A Sermon, delivered May 9, 1798: recommended, by the President of the United States, to be observed as a day of general humiliation, fasting, and prayer. classicapologetics.com

- John Prince, Salem: A Discourse, delivered at Salem, on the day of the national fast, May 9, 1798; appointed by President Adams…[13]

So that you can get a taste of the flavor of what these proclamations produced, here is an excerpt from Jeremy Belknap’s sermon:

“This separation and the establishment of our independence, were the result of causes, foreseen and foretold by Him, to whom all his works, and all the operations of inferior agents, are perfectly known from the beginning of the world. All the wisdom of statesmen, all the eloquence of orators, and all the strength and power of fleets and armies could not counteract the decree of Heaven, that America must be separated from Britain. From the experience which we have had of her conduct, it is my most earnest wish, and from our own increasing power and resources and the wisdom and stability of our present government, it is my confident expectation, that the separation will ever remain, and that we shall be an independent people, fully equal to the business of governing ourselves, without any foreign interference whatever. If there be any persons among us who are for re-uniting us with Great-Britain, I hold their political principles in as much abhorrence as those who are for subjecting us to the influence of France; for I detest the thought, that any rotten toe of Nebuchadnezzar's image, or any proud horn of the seven-headed beast, should ever exercise dominion over this country.”

c. Sacred Time in the Civic Calendar

The Federalist proclamations landed in a world that already treated fasts and thanksgivings as civic holy days. In the seventeenth century, New England Puritans had stripped away the old saints’ days and feast days, but they did not abandon sacred time; they replaced the liturgical year with these occasional public fasts and thanksgivings proclaimed in response to judgment or mercy. But by the early eighteenth century, Massachusetts and her sister colonies had settled into a regular pattern: a spring fast day to seek God’s favor on the coming season, and an autumn thanksgiving to mark harvest and deliverance.

By the era of Washington and Strong, that “occasional” practice hardened into a bi-annual rhythm: a spring fast to humble the community before God, and an autumn thanksgiving to mark harvest and deliverance; this was a calendar the Federalists inherited and then filled with their own theology of nationhood. These proclamation days became essentially an extra Sabbath in the middle of the week, with suspended labor, church attendance, and then finishing with a reverent family meal. When National and State Magistrates called for national days of “public humiliation, fasting and prayer,” they were not inventing a new civic ritual but nationalizing an existing one.

VI. Jefferson & Madison: A Limited Government Approach

On the Anti-Federalist side, Jefferson and Madison provided their pushback on constitutional grounds; they did not consider it within the purview of the magistrate to make such proclamations. Anti-Federalists sought to limit federal power out of concern about federal overreach. They took a very restricted approach, seeking to keep government out of the business of prescribing religious exercises, thereby leaving such things to the local church.

In 1808, Jefferson declined to issue national fast or thanksgiving proclamations on the ground that the Constitution “interdicts” the federal government from “intermeddling with religious institutions” and that no power had been delegated to prescribe any religious exercise.

In the Detached Memoranda (1820), Madison went further: even non-binding presidential “recommendations” risk a soft establishment by putting national authority behind a religious rite, subtly pressuring conscience and inviting partisanship.[14]

Federalists answered that encouragement was not establishment. A proclamation neither founds a church nor denomination but rather serves to clear civic time (abstain from labor, assemble for worship) so that churches and households may worship according to their own forms. On this view, the magistrate’s office includes moral suasion: publicly acknowledging God, calling the people to gratitude and repentance, and asking the Lord’s blessing on rulers and laws while doctrinal instruction remains with the pulpits.

Two civil-religion models emerge: Federalist—public Christianity as moral infrastructure for republican life; Jeffersonian/Madisonian—religion privatized to protect liberty. The evidence of the 1790s–1810s shows which model actually led to national Christianity by consecrating holy days, inspiring pulpits, and binding the people together as a united Christian nation.

VII. What the Federalists Built and What We Can Recover

These proclamations were exactly what the young American nation needed in order to unite as a people for their earthly and heavenly good. Ordering them to acknowledge their Creator and Giver of every good gift was Christian Nationalist statecraft in the form of public liturgy. Washington’s 1789 proclamation named the 'great Lord and Ruler of Nations’ and cleared time for worship; Adams’s fasts in 1798 and 1799 seeded pulpits with particular sermons; Jay and Strong translated the same script to New York and Massachusetts, calling for assembly, abstaining from work, and rendering repentance and thanks to God.

The effect was tangible: markets closed, pews filled, pulpits enflamed with the Holy Spirit teaching the nation to structure its life under Providence. Jefferson and Madison argued for a narrower federal role, but the Federalists answered that encouragement is not establishment; in their view, the magistrate could summon gratitude and repentance while leaving doctrine to the churches. In that cadence, Americans learned civic prayers. As Washington put it, it is the ‘duty of all Nations to acknowledge the providence of Almighty God,’ and for a formative span of our early life, we did so together. So, on this Thanksgiving day in the Year of our Lord, 2025, let us adhere to the traditions of our forefathers with repentance and thanks.

VIII. Epilogue: Hammond, Charleston, and the Jews

In my research, I stumbled upon a proclamation many years after the Federalist Era that was explicitly and exclusively Christian, which received particular backlash from Charleston's Jewish community. South Carolina Governor James Hammond named Thursday, October 3rd, 1844, as a day of thanksgiving and prayer. In his proclamation, he made reference to "all Christian nations," and went on to "invite and exhort our citizens of all denominations to assemble at their respective places of worship, to offer up their devotions to God their Creator, and his Son Jesus Christ, the Redeemer of the world."

This proclamation brought on a strong backlash from the oldest Jewish community in America based in Charleston. They wrote a letter of protest and demanded an apology, claiming the proclamation was "unusual" and "offensive." Governor Hammond stood his ground, in what could be seen as tongue-in-cheek saying, "I have always thought it a settled matter that I lived in a Christian land," and "it did not occur to me, that there might be Israelites, Deists, Atheists, or any other class of persons in the State who denied the divinity of Jesus Christ."

Now, being that Hammond's own President, Jefferson, was a deist who called the Trinity a "hocus-pocus phantasm of a god...with one body and three heads" in 1822, this seems like a bold quip, asserting Christianity as the only true religion and acting as though this was self-evident even though he knew it not to be the uniform belief of Americans. But even if he truly was acting in ignorance, he went on to say, he would not have changed the language: "I have no apology to make for it now."[18]

And neither do we.

Sources

- Edward Winslow, in Mourt’s Relation: A Journal of the Pilgrims at Plymouth (London, 1622). For a modern transcription, see “Mourt’s Relation,” esp. the harvest passage beginning “Our corn did prove well, and God be praised, we had a good increase of Indian corn.” HistArch+1

- On colonial and early national fast and thanksgiving days as recurring civic holy days, see John R. Vile, “Proclamations of National Days of Prayer or Thanksgiving,” First Amendment Encyclopedia, which traces colonial and Continental Congress precedents for such observances. The Free Speech Center+1

- Jonathan Trumbull, A Proclamation, for a Day of Fasting and Prayer (Connecticut, 1770s). For an example of Trumbull’s fast-day language, see the Connecticut broadside “A Proclamation, for a Day of Fasting and Prayer” in the state and library catalog records. NYPL Borrow+1

- Annals of Congress, 1st Cong., 1st sess., 25 September 1789, 914–15. Elias Boudinot introduced a resolution that a joint committee “wait upon the President of the United States, to request that he would recommend to the people a day of public thanksgiving and prayer… especially by affording them an opportunity peaceably to establish a Constitution of government for their safety and happiness.” Founders Online+1

- On Aedanus Burke’s objection that a national thanksgiving was “European” and akin to both sides of a war singing Te Deum, see discussion of the 1789 thanksgiving debate in the scholarship on Washington’s first proclamation and congressional debates over the resolution. Hudson Institute+1

- Thomas Tudor Tucker’s objections appear in the same House debate on September 25, 1789, recorded in the Annals of Congress, where he argued that if a thanksgiving were to be held, it ought to be by the authority of the states rather than the federal government. Kathrine R. Everett Law Library+1

- Thomas Jefferson to Samuel Miller, 23 January 1808, in The Works of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 11, or in the Founders Online edition, where Jefferson writes, “I consider the government of the US. as interdicted by the constitution from intermeddling with religious institutions, their doctrines, discipline, or exercises… certainly no power to prescribe any religious exercise, or to assume authority in religious discipline, has been delegated to the general government.” Berkley Center+3Founders Online+3Americans United+3

- George Washington, “Thanksgiving Proclamation,” 3 October 1789, in Founders Online and the National Archives, beginning, “Whereas it is the duty of all Nations to acknowledge the providence of Almighty God…” and designating Thursday 26 November 1789 as a day of public thanksgiving and prayer. Founders Online+2George Washington's Mount Vernon+2

- George Washington, “Proclamation, 1 January 1795,” recommending Thursday 19 February 1795 as “a day of public Thanksgiving and prayer” and referencing the suppression of “the late insurrection” (the Whiskey Rebellion). Founders Online+2Avalon Project+2

- John Adams, “Proclamation for a Day of Fasting, Humiliation and Prayer,” 23 March 1798, and “Proclamation—Recommending a National Day of Humiliation, Fasting, and Prayer,” 6 March 1799, both of which stress that “the safety and prosperity of nations ultimately and essentially depend on the protection and the blessing of Almighty God.” Miller Center+2American History+2

- George Washington, diary entry for 26 November 1789: “Being the day appointed for a thanksgiving I went to St. Pauls Chapel though it was most inclement and stormy—but few people at Church,” in Founders Online: The Papers of George Washington. Founders Online+1

- Stephen Decatur Jr., Private Affairs of George Washington: From the Records and Accounts of Tobias Lear, Esquire, His Secretary (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1933), drawing on Lear’s records for Washington’s donations of “provisions and beer” to debtors imprisoned in New York. Google Books+2HathiTrust+2

- For printed fast-day sermons responding to Adams’s 9 May 1798 proclamation, see for example:

- Jeremy Belknap, A Sermon, Delivered on the 9th of May, 1798, the Day of the National Fast, Recommended by the President of the United States (Boston: Samuel Hall, 1798);

- Jedidiah Morse, A Sermon, Delivered at the New North Church in Boston, in the Morning, and in the Afternoon at Charlestown, May 9th, 1798: Being the Day Recommended by John Adams… for Solemn Humiliation, Fasting and Prayer (Boston: Samuel Hall, 1798);

- Thaddeus Mason Harris, A Sermon Preached in Milton on the Morning and at Dorchester in the Afternoon of the 9th of May, 1798: Being the Day Recommended by the President of the United States for Solemn Humiliation, Fasting, and Prayer Throughout the Union (Boston, 1798);

- Samuel Miller, A Sermon, Delivered May 9, 1798: Recommended, by the President of the United States, to Be Observed as a Day of General Humiliation, Fasting, and Prayer (New York: T. and J. Swords, 1798);

- John Prince, A Discourse, Delivered at Salem, on the Day of the National Fast, May 9, 1798: Appointed by President Adams, on Account of the Difficulties Subsisting Between the United States and France (Salem, 1798). SSHELCO Primo+11Google Books+11Clarin VLO+11

- James Madison, “Detached Memoranda” (ca. 1817–1832), especially the sections criticizing presidential religious proclamations as tending toward “establishment,” in The Founders’ Constitution and in the First Amendment Encyclopedia overview of the Detached Memoranda. W&M Law School Scholarship Repository+3University of Chicago Press+3The Free Speech Center+3

- Caleb Strong, By His Excellency, Caleb Strong, Governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, a Proclamation, for a Day of Public Fasting, Humiliation and Prayer (Boston, 1806), which includes petitions for unity, the success of the gospel, and the prosperity of commerce, manufactures, fisheries, and schools. University of Rochester Libraries

- Caleb Strong, By His Excellency, Caleb Strong, Governor of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, a Proclamation, for a Day of Public Fasting, Humiliation and Prayer (Boston, 1813), calling on the people to beseech God “that He would establish his Covenant between Him and us, and our children after us, for an everlasting Covenant,” and invoking “that grace and truth which came by Jesus Christ.” State Library of Mass

- John Jay, Thanksgiving Proclamation, 19 February 1795 (New York), beginning “Whereas the Great Creator and Preserver of the Universe is the Supreme Sovereign of Nations…” and urging public thanks and petitions for the extension of “true Religion, Virtue and Learning.” See analysis and quotations in Daniel L. Dreisbach, “John Jay: The First Chief Justice,” in Great Christian Jurists in American History (Cambridge University Press, 2019). Cambridge University Press & Assessment+1

- James H. Hammond, Thanksgiving Proclamation (South Carolina, 1844), calling on citizens to worship “as becomes all Christian nations” and invoking “their Creator, and his Son Jesus Christ, the Redeemer of the world,” and the subsequent protest from Charleston’s Jewish community, who objected to the explicitly Christian language. See Jonathan D. Sarna, “Christians and Non-Christians in the Marketplace of Religion,” which reproduces the key language of Hammond’s proclamation, and coverage of the controversy in modern summaries of South Carolina’s Thanksgiving history.

ATTENTION READER: We need your help.

Institutional trust is at record lows. But without institutions, we cannot renew our people, much less provide an inheritance to posterity. In response to this crisis and as an organic outgrowth both of necessity and natural interest, American Mantle exists. And so we make our appeal.

Donate to the Cause. Help us reach our monthly goal in order to solidify this crucial institution.