Holocaustianity: A Counterfeit Creed

Thus enshrined by remembrance and precept, the legacy of World War II, history’s fiercest conflagration, birthed a new doctrine of good and evil, with the Holocaust at its heart, that now stands as humanity’s latest attempt to forge a new global religion.

“I guess we’re all Nazis now,” my mother quipped with a wry chuckle, browsing Facebook where her Baby Boomer peers—Republicans and Democrats alike—exchanged “Nazi” slurs in their political spats. Godwin’s Law, coined by Mike Godwin in 1990, says that as internet discussions lengthen, the likelihood of a Nazi or Hitler comparison nears certainty, derailing debates and trivializing serious issues. This reflex to brand opponents “Nazis” reveals a narrative so ingrained that even Christians rely on its moral framework.

The name “Hitler” has become universal shorthand for evil, surpassing “Satan” in our cultural lexicon. Yet this universal shorthand extends beyond online squabbles, reshaping the moral imagination of our culture and churches. Across the Christian spectrum, from liberal congregations lauding moral revisionism to conservative churches grieving it, one shared conviction unites us all: Adolf Hitler embodied profound evil, the Nazis served his vile agenda, and the Holocaust remains a sacred wound on humanity’s hands and side, demanding our reverence, repentance, and remembrance... or at least our abuse of it as a political cudgel.

Despite the modern tendency to trivialize serious matters for political ends, deeper discussions of the Holocaust still prompt sober reflection on a singular tragedy. In schools, Holocaust studies incur such trauma to the human mind that they prompt questions about God’s goodness, or even his existence. In pulpits, the Holocaust’s moral weight provides rhetorical fuel for fervent sermons, sparking action on other moral causes: Pro-life advocates label abortion an “American Holocaust,” leaning on its rhetorical power; defenders of religious liberty link secular laws to “Nazi tyranny,” spurring action among the faithful; and would-be prophets warn of a “new Holocaust” amid rising persecution, urging vigilance against blissful naivety. These cries, though zealous, lean heavily on a secular narrative’s gravitas, threatening to exalt a temporal sorrow above the Cross’s eternal witness.

As conservative Christians, we uphold Scripture alone as our decisive standard, our light in a darkened world. We mourn when schools reshape young souls to reject God’s created order; we lament when churches blend social grievance with the gospel. Yet, what if this spiritual drift stems from a quasi-religious narrative we’ve all accepted unexamined? What if, in our zeal for empathy, we’ve embraced a doctrine untested by Scripture’s light? I do not aim to downplay war’s horrific toll or stir unwarranted conflict, but I must ask: Have the Holocaust’s moral and spiritual lessons become new doctrines, rivaling historical Christian theology?

In the grip of the Holocaust’s searing trauma, sincere Christians, driven by profound empathy, embraced new principles untested by God’s Word, risking the compounding of evil through well-meaning but errant reactions. The urgent cry of “never again,” for example, has caused modern Christians to look at Church history, national distinctions, and even Scripture itself through a Holocaust-colored lens, bending theology and social policy away from historical Christianity. Such trauma-driven responses, though well-intentioned, risk repaying evil for evil, compounding the initial pain. Proverbs 14:12 warns, “There is a way which seemeth right unto a man, but the end thereof are the ways of death.” We must heed this wisdom, lest our sorrow in response to tragedy blurs our vision, causing us to betray biblical truths, harming souls and nations as we stray onto an errant path, unlit by the word of God.

The early and medieval Church faced similar syncretistic snares. Early Christians grappled with the error of blending pagan philosophies with the Gospel, prompting Paul’s warning: “Beware lest any man spoil you through philosophy and vain deceit, after the tradition of men, after the rudiments of the world, and not after Christ” (Colossians 2:8). Martin Luther, opposing unbiblical dogmas at the Diet of Worms in 1521, proclaimed, “Unless I am convinced by Scripture and plain reason, my conscience is captive to the Word of God.” Scripture calls us to “Prove all things; hold fast that which is good” (1 Thessalonians 5:21). Beloved of God, let us open our Bibles, honor our fathers in the faith, pray for wisdom, and seek Christ together, discerning whether our postwar principles glorify our Savior or tie us to a darkened, worldly creed.

The Rise of a Mythologized Narrative

How did the suffering of the Jews in World War II ascend to a moral touchstone, not just in the world but in our churches? After the war, harrowing images of emaciated prisoners and testimonies of Nazi horrors afflicted the global conscience. Postwar books and films, from Anne Frank’s Diary to Schindler’s List, secured the Holocaust narrative as a defining parable of good versus evil, surpassing other historical griefs in cultural impact. Today, we denounce wickedness by summoning Nazis; we inspire courage by recounting Jewish resilience and the heroes who defied peril to aid them. Israel’s Yad Vashem World Holocaust Remembrance Center enshrines the Holocaust as a hallowed cornerstone, and nations like Germany and France criminalize questioning its core claims. The story of the Holocaust is no longer a mere question of history; it has become a mythologized allegory, imbued with moral and spiritual weight, fostering human unity with a modern creed against all ethnic divisions, etched into our collective soul through sacred sites and pervasive storytelling.

This modern creed found permanence in a rapid proliferation of Holocaust memorials, covering reported Nazi extermination camps, all located in Soviet-aligned Poland post-war. Memorialization began in 1947 with the Auschwitz-Birkenau and Majdanek State Museums, followed by the Warsaw Ghetto Monument in 1948, each initiated by communist Poland’s Soviet-influenced Ministry of Culture and Art. Supported by Jewish survivor groups, these efforts aimed to preserve and showcase reports of atrocities by Nazi Germany—communism’s wartime foe. From 1947 to 1955, early Auschwitz exhibitions also showcased anti-Western depictions of American urban poverty to equate capitalism with Nazism, reflecting Cold War efforts using postwar propaganda to bolster communist regimes. The founding of Yad Vashem in Israel, in 1953, elevated the memorialization globally, canonizing the reported six million Jewish victims as a sacred legacy for their new state. Further monuments arose at Buchenwald in communist East Germany in 1958, followed by Treblinka and Sobibor in communist Poland in the mid-1960s. After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, memorialization expanded with the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C., in 1993, alongside revisions like Auschwitz’s 1990 death toll adjustment from 4 million to 1.1 million—a shift that, curiously, left the six-million Jewish death toll unaltered in the postwar consciousness. In the 21st century, memorialization surged with sites like Berlin’s Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in 2005, Shanghai’s Jewish Refugees Museum in 2007, and Amsterdam’s National Holocaust Museum in 2024. Today, Holocaust memorials and museums have arisen across at least 46 nations—from Argentina to Australia, Belarus to Brazil, Croatia to Canada, and beyond to China, South Africa, and Mexico—forging a global mandate to educate and commemorate, embedding the narrative’s moral imperatives into cement and steel.

This institutional enshrinement was amplified by a torrent of Holocaust-related media, beginning with survivor accounts like Eugen Kogon’s Der SS-Staat, in 1946, Primo Levi’s If This Is a Man, in 1947, and fictional works like John Hersey’s The Wall, in 1950, each weaving the reported Nazi persecution into global consciousness. The 1960s and 1970s brought historical studies like Raul Hilberg’s The Destruction of the European Jews, in 1961, and dramatizations like the miniseries Holocaust, in 1978, which burned the narrative into public memory. Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah, in 1985, Art Spiegelman’s Maus, in 1986, and Steven Spielberg’s fictional masterpiece, Schindler’s List, in 1993, blended testimony and storytelling, establishing the Holocaust story as a parable of good versus evil. In 2012, Robert and Carol Reimer’s Historical Dictionary of Holocaust Cinema listed over 600 Holocaust-related films, documentaries, and television productions, demonstrating the narrative’s profound reach in modern media. In the digital era, works like Ken Burns’ The U.S. and the Holocaust, in 2022, and The Zone of Interest, in 2024, continue to shape moral imaginations, ensuring the narrative’s enduring grip on hearts and minds and fortifying it against those who dare question its claims.

This fortification of the Holocaust’s sanctity was shielded by a relentless campaign of legal persecution against those who challenged its tenets, etching its inviolability into the conscience of nations. In 1949, French writer Maurice Bardèche faced fines and a suspended prison term for his denialist book Nuremberg ou la Terre Promise, marking an early strike against dissent. The 1980s saw Canada’s Ernst Zündel convicted in 1985 and 1988 for his pamphlet Did Six Million Really Die?, while Britain’s David Irving lost a libel suit against Deborah Lipstadt in 2000 and was imprisoned in Austria in 2006 for denying the reported mass murder. Recent cases, like Vincent Reynouard’s 2023 extradition from Scotland to France for online denialist videos and Andrew Torba’s 2025 ban from the UK and European countries for allowing denialist content on Gab, reveal an unrelenting global resolve to silence skeptics, casting their questioning as a moral blasphemy against humanity’s new creed.

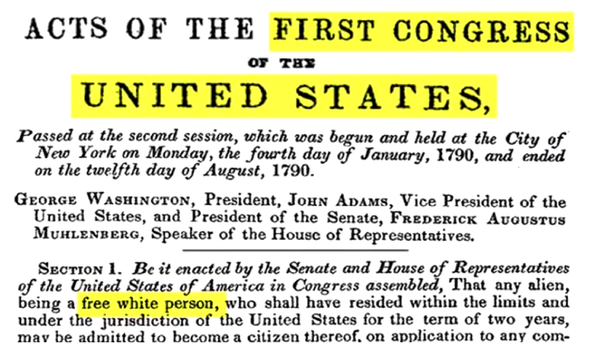

Such punitive zeal was codified in a global lattice of laws that rendered dissent a secular crime akin to heresy, further enshrining the Holocaust’s untouchable status. Israel’s Denial of Holocaust Law in 1986, France’s Gayssot Act in 1990, and Germany’s expansion of Section 130 in 1994 set the precedent, criminalizing denial with fines and imprisonment. The European Union’s 2008 Framework Decision prompted seventeen member states, including countries such as Austria, Belgium, Portugal, Hungary, and Romania, to enact specific anti-denialist laws still enforced today. These statutes, born of post-war fervor, transformed the Holocaust into a doctrine beyond scrutiny, where questioning its claims is not merely error but criminal heresy, exacting atonement through legal and social retribution and reinforcing its creedal authority as a political dogma that brooks no challenge.

Thus enshrined by remembrance and precept, the legacy of World War II, history’s fiercest conflagration, birthed a new doctrine of good and evil, with the Holocaust at its heart, that now stands as humanity’s latest attempt to forge a new global religion. The term “holocaust,” originating from the Greek holokauston and transmitted through the Latin holocaustum (as found in the Vulgate, Leviticus 1:3–9), refers to a sacrificial burnt offering entirely consumed by fire, denoting deep spiritual significance. Applied to Jewish suffering, it creates a sacred atmosphere, where questioning its importance becomes a sin against humanity, and where affirming its frame signals humanitarian virtue. The post-war narrative casts Hitler as the quintessence of inhumanity, surpassing the devil in our social imagination. Christians, seeking to integrate this powerful narrative, weave it into theology: some Christians say Hitler despised Christ and denied the Imago Dei in mid-century Jews; some charismatics suggest he was demon-possessed, driven by unseen legions; some Christian Zionists view him as a shadow of the Antichrist, as Israel’s penultimate foe. Given the cultural dominance of the post-war narrative, better known to the modern public than any New Testament parable, it’s unsurprising that this 20th-century parable shapes our moral framework. Rooted in the psychological shock of wartime atrocities, it demands eternal remembrance of a historical travesty now held sacred, with vital moral lessons humanity must never neglect, regardless of race or creed.

Christian evangelist Billy Graham, standing at Auschwitz in 1978, was indelibly seared by Holocaust accounts, declaring, “The memory of the incredible horror which took place here will be burned on my heart and mind as long as I live... Auschwitz is more than a place. It is a blot on the whole human race… a systematic crime against all moral and spiritual values.”. Such words from a beloved evangelical preacher reveal how stories of the Holocaust indict humanity, calling for global atonement through remembrance of reported atrocities. The urgent call for humanitarian penance, shaped by post-war testimonies in Soviet-aligned Poland and Eastern Germany, originated from far outside the church. Yet, when pliant empathy hardens into a sacred creed, it risks rivaling biblical truth in believers’ hearts. Have we tested this modern paradigm against Scripture’s standard, as Christ requires through corroboration (John 5:31) and discernment (1 Thessalonians 5:21)? Or have we allowed its piercing traumas to cloud our judgment, etching with a hot iron a modified conception of good and evil on our conscience?

The late Catholic Bishop Richard Williamson, with words that resonate sharply even after his passing, exposes the deceptive allure of this new creed:

The new religion is very seductive. It's very soft and sweet and sticky. And it's easy to go with it and lose the Catholic faith. You have a new and different faith. A happy-clappy faith, where everybody's nice, everybody's sweet… The only sin that’s still left is “Nazi” sin… Hitler is the devil. The Six Million are the redeemer… And that’s deadly. It’s got nothing to do with the Catholic faith, except that it’s a clever imitation… because you get Auschwitz instead of Golgotha, and the Gas Chamber instead of the Cross. That’s deadly… Can I blaspheme our Lord Jesus Christ? Does anybody worry? No problem. Blaspheme as much as you like. Can I blaspheme against the Holocaust? “Horror! Horror! He’s a heretic!” There you can see the real religion of the government today, of politics today, and of the mass of the people today.

This modern paradigm profoundly weakens the church. Where Christendom’s kings once spread the gospel globally by the Spirit of God, today a different spirit advances a creed of global pluralism, centered on a new Golgotha built on guilt, not grace. As we mourn the suffering caused by human conflict, let us avoid any doctrine that rivals Scripture, reject any narrative that rivals Calvary, hold fast to Scripture as our sure guide, and cling to the Cross as our sole salvation.

Profiting from the content? Donate to the Cause.

Helps us reach our monthly goal.