Folk and Folkdom: A Review in Three Movements

We can speak about folk, boundary, body, continuity, and moral order without falling into either absolute race-myth or administrative deracination.

Theodor Grentrup (1878–1967), born in Ahlen, Westphalia, to a family of weavers, was a German Roman Catholic priest of the Society of the Divine Word (SVD). He entered the order in 1893 at Steyl, professed final vows in 1901, and was ordained in 1902. After earning his doctorate in canon law in Rome in 1905, he taught at the SVD's St. Gabriel mission seminary in Austria, where he became a leading voice in missiology. His groundbreaking 1925 book Jus Missionarium pioneered the integration of canon law with international law to protect missionary rights and cultural freedoms in non-Christian lands.

Over decades, Grentrup produced more than sixty works, shifting focus after World War I to the legal and pastoral rights of ethnic and linguistic minorities—especially German diaspora communities—while defending human dignity amid displacement and political upheaval. In Folk and Folkdom in the Light of Religion (1937), he offers a careful Catholic reflection on folk identity, race, and national life, insisting that genuine folk-community must be purified, elevated, and ordered under transcendent divine grace rather than absolutized or divinized. A tireless advocate for the vulnerable, he later turned his energies to the pastoral care of postwar refugees, embodying a missiological commitment to both natural rootedness and revealed religion.

Theodor Grentrup’s Folk and Folkdom in the Light of Religion is valuable for a reason that does not announce itself on the first page: it restores moral and conceptual seriousness to terms that modern politics has degraded into shibboleths and slogans. “Folk,” “race,” “religion,” “truth”—words now used either as sentimental ornaments or as instruments of coercion—are returned to their proper weight and relations. Grentrup does this without the modern habits of panic and euphemism, advancing like a surveyor to make slow, exact distinctions that remain intelligible under stress.

This matters because the subject is not picturesque. Folk life is where nations actually live or die—where continuity is reproduced, where inheritance is transmitted, where moral expectations are enforced, and where loyalties are formed before politics ever touches them. You can build administrative order on top of a people for a time, and you can finance a simulacrum of unity, and you can flood a culture with entertainment meant to dissolve memory; but, if the underlying substance is hollowed or turned against itself, or if it bears no relation to the divine, or worse, is actively hostile to it, then you are left with a metaphysical mess. Grentrup writes as though he understands this. His tone is measured; his stakes—religion and natural, collective identity—are not.

What follows is a refactoring of the work in three movements—nature, religion in general, and Christianity in particular—with emphasis on the parts that offer genuine ballast for anyone trying to imagine national life without either romantic intoxication or bureaucratic sterilization.

I. Folk, Folkdom, Bodily Form, Ethical Evaluation

Part One is the book’s foundation, and it is stronger than it appears at first glance. Grentrup refuses to begin with a rallying cry or a narrative hook. Instead, he commences with descriptions that force your mind to slow down: a folk is not a slogan, nor is it a single marker; it is a lived human community with a real interior shape. Folkdom names that interior shape—the spiritual-cultural form a people acquires through time, expressed in language, custom, moral reflex, artistic sensibility, shared conviction, and inherited styles of feeling and judgment. It is “soulful” in the old sense: not a mystical fog, but an inner cohesion that becomes visible in outward life.

Two features of his approach stand out.

First, his concept of the folk is built around growth and continuity rather than theory. He keeps returning to the basic facts that cosmopolitans prefer to treat as embarrassing: generational succession, family expansion, the thick texture of collective life, the quiet force of blood-bond and mother tongue, the way common fate and shared memory shape a people into something more durable than the sum of the private individuals. He treats the folk as emergent—its powers specially germinate within these bonds—yet he never turns it into an untouchable idol. It can be malformed. It can be corrupted. It can be disciplined. It can be evaluated. That last point is crucial: he preserves room for moral judgment without dissolving the folk into abstraction.

Second, he has an unusually sane handling of bodily form and race. He refuses to pretend embodiment is irrelevant, as he likewise refuses to treat it as metaphysical destiny. Race matters as an “iron framework” of embodied difference—affecting dispositions, aesthetic senses, habitual temper, and lived compatibility—but race does not exhaust the folk, and a folk’s coherence is not reducible to a purity myth. “Harmony” becomes the operative word here—harmony within what is often a composite picture, a practical coherence tested and proved by lived affinities rather than by intellective daydreaming.

Folk-life, Grentrup argues, is a "greater form of life" than individual life, though it is composed of individuals. But folk-life is neither a mere expansion of the individual, nor does it possess only what individuals can give to it. Rather, it is unique, possessing a "truly... new life" which would otherwise remain dead in the soil of the individual soul but within the folk is awakened and employed. The folk brings "plants to germination and fruits to ripen" among men, where "nature is shaped into its full image"—the needed community for man as social creature, into which "every man finds his place" and is "born without a choice." Its "primal cell" is the family, driven by instinct and nature. Its chief characteristics are: first, blood kinship; second, its quantitative and qualitative greatness, in population size and spiritual-cultural achievement; and third, spiritual bond. Yet, the folk in all respects is not subject to purely rational interpretation. Grentrup seems to grant it something mystical. With respect to religion, the folk must conform to the true, the good, and the beautiful; thus, the question "does not depend on whether the Folk has its own distinct religion; rather, it depends on whether it has a true religion of its own kind." Grentrup is clear that "the Creator of nature has planted the becoming of the Folks in the germ and has willed [them] in the final outcome."

Folkdom, as distinct from yet closely related to and sometimes equated with folk, is something else. It is the "distinct soulful-spiritual expression" of a distinct folk, as witnessed in various particulars such as art, language, poetry, dress, and custom—often what we today might call culture. Not religion proper, but religious expression combined with the folk's attitude toward religion, belong to folkdom. And just as folk is not the sum of individuals, folkdom is not a "bundle of individual phenomena"; it has its own unity and identity. Folkdom certainly has an external expression; but this external expression is rooted in the "inner constitution" of the folk itself. Further, its core is composed of "geistance"—a triad of conviction, spirit, and attitude, which is both naturally and freely formed. Grentrup in this section makes clear that he is no pietist: he says that great "leader-personalities" and "a powerful state" are necessary to secure and safeguard folkdom and thereby the folk from fatal softening.

The book quietly resists two common errors by refusing to grant either of them a monopoly on realism. Vulgar purism is checked by the observation that serious peoples are rarely ethnically singular in a simplistic way. On the other hand, liberal mixing—casual, large-scale, moralized through abstractions—is checked by an equally unflinching observation: small admixtures can be absorbed into a strong stream, but large influxes provoke instability, resentment, repulsion, and disorder. Grentrup speaks as though he is describing a law of social physics; you may dislike the conclusion, but your dislike does not repeal the mechanism. He even notes bodily shifts over long time—skull-forms rounding over centuries, diaspora differences—without claiming that folk-essence shatters automatically. The implication is as bracing as it is useful: cultural-spiritual continuity can outlast measurable bodily drift, yet bodily realities still set constraints and pressures that wise societies ignore at their peril.

Further, while Grentrup grants the supremacy of spirit and spiritual values over the physical, at the same time he does not dichotomize body and spirit, nor does he devalue the physical. The "ideals of honor, fidelity, and devotion to Folk and Fatherland" outshine the ideals of "bodily strength and agility." Yet both will be necessary, he implies, in order to defend the German Folk and her "goods of life and faith" in the "coming gigantic struggle of spirits and bodies" between "Western Christian culture" and "godless Bolshevism."

The ethical chapter is the capstone to part one, and it deserves particular attention. Grentrup’s ethic is not a maudlin “affirmation” ethic. Folkdom is not self-justifying. Idiosyncratically, nature, for Grentrup, is twofold—both created and fallen, where both wheat and chaff grow together. Loyalty, therefore, is fidelity to the better self rather than indulgence in whatever may happen to emerge. He invokes sequere naturam—follow nature—but nature here is not an invincible totem; rather, it is a field that requires cultivation and pruning. Tradition must be honored without being fossilized. And Christianity, which comes into view more explicitly later, is already present here as a horizon: creation and providence illuminate the folk’s givenness, its talents, its historical path, without erasing its powers of freedom and need for struggle. Grentrup’s optimism is guarded, and that is part of his credibility. As Scripture teaches, the righteous man falls seven times; so, too, can the folk. And therefore discipline remains necessary.

What Part One gives a serious reader is conceptual clarity that does not collapse under moral pressure. It distinguishes community from society without writing fairy tales about either. It affirms rooted continuity without denying imperfection, restoring the legitimacy of boundaries without sacrificing moral order to boundary-worship, where the reader can defend the substrate without deifying it.

II. Folk and Religion in General

Part Two turns from the folk as natural order to the folk before God, and Grentrup’s handling here is one of the quiet strengths of the book. Then-contemporary movements made attempts to relate or even fuse the divine with the folk—sometimes poetically, sometimes philosophically, sometimes politically. Grentrup takes this fact (and underlying inclination) seriously enough to map it carefully. He lets Fichte, Hegel, Herder, Lagarde, Dostoevsky’s Shatov, and others speak long enough that the reader can feel the attraction. And then he draws the line where it must be drawn if anything like Christianity is to survive: if divine substance collapses into folk-substance, transcendence evaporates. The folk becomes the highest court. There is no external correction. The demonic has no judge above it. Moral striving loses its ultimate standard and turns into self-justifying energy, where the folk is not elevated but straitjacketed.

He extends the critique by testing the consequence most writers avoid: divine attributes. If folk and God merge in essence, then classic divine attributes like holiness, omnipotence, eternity, and omniscience must attach to the folk. No serious thinker can hold that consistently because reality and logic refuse it. Grentrup therefore makes a fine distinction that becomes structurally important later: the folk bears an "image" of the eternal—roots in prehistory, fullness across life-stages, future creative seed, and the collective of Man, who, as Scripture teaches, is made in God’s image—yet the folk remains perishable and bounded. The “eternal folk” rhetoric might rightly function as emotional summons to inspire permanence, love, and defense; as ontology it fails.

His most incisive work in this part is on religious truth. He is explicit: truth cannot be derived in its ultimate origination from blood, character, or folk-disposition. Folk-types may shape the style and imagery of piety; they do not generate universally valid propositions about God. The German-Believers who denounce dogma as alien fetters merely smuggle in their own dogmas and demand assent. Experience requires correspondence to reality. Religious cognition occurs in individual minds, shaped by history and environment, and subject to the possibility of error. A “race-truth” would fragment into mutually exclusive absolutes—or into countless private truths. Christianity’s independence here becomes its power: revelation comes from above; it judges, receives, and elevates nature precisely because it is super-nature.

The concluding chapter on religiosity returns the argument to lived life. Communal prayer and song, cathedrals as folk-thoughts of God, roadside crosses and harvest thanksgivings—these are particular folk-forms that arise organically within a people and can be purified rather than annihilated. Grentrup acknowledges that folk-character and religion co-shape one another, whether in fatalism and defiance here, or providential trust and inward reserve there. He also notes variation within Christianity—Polish fervor and German reserve, for instance—without sliding into relativism. Each carries gifts and dangers. None can claim to be the measure of all.

Part Two, taken whole, accomplishes something difficult: it blocks pantheistic absorption without flattening folk distinctiveness into sterile abstraction. Transcendence is not dissolved but preserved, and thereby it keeps the folk from becoming its own god, while still leaving room for a folk-shaped piety that is genuine and valuable rather than counterfeit.

III. Folk and Christianity in Particular

Part Three is the culmination: how a folk's independent life encounters Christianity as revealed faith and institutional reality. Grentrup’s argument here is more consequential than it first appears because it answers—without shrillness—a claim that haunts modern discourse: that Christianity is inherently dissolving, universalist in the sense of leveling, and especially hostile to distinct peoples and their ways of life. He does not answer by sentiment; instead he answers by calling three witnesses: Scripture, ecclesial logic, and historical practicality.

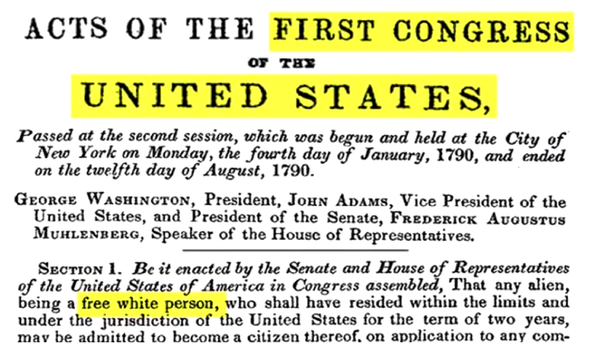

Scripture, he argues, affirms the plurality of folks as divine order within creation, which means that differentiation across the earth is not an accident to be apologized for. Babel, Acts, and Pentecost attest to this. The one revealed truth of Christ does not require the annihilation of tongues or of folks. Pentecost is especially germane: rather than “reversing Babel” as some today foolishly claim, it marks a unity of proclamation through a multiplicity of languages, where distinct folks are touched and converted by the Spirit of God through their distinct mother tongues. Yes, there is equality in Christianity, but an equality before God which pertains to the domain of soteriology, i.e. to access to Christ and his saving benefits. This, however, does not negate natural inequalities in gift, achievement, and historical role. Those are judged in the world.

Grentrup then treats the Church as visible institution with its own order—teaching, sanctifying, governing—while refusing the confusion that makes either side total. The Church does not swallow folk-life, and folk-life does not dictate doctrine. Their independence is real, and their mutual limitation is fruitful when rightly ordered. Practical examples matter here. Grentrup cites concordats that protect mother-tongue worship for minorities abroad, the ways ecclesial structures can defend folk continuity under foreign states, and the manner in which “universality” does not mean homogenization of rite, language, or custom. In other words, Grentrup grounds his distinctions in institutional realities rather than leaving them as airy principles.

The final chapter synthesizes the relation: commitment to the Church elevates what is authentically one’s own rather than erasing it. Grace assumes nature. The Church’s task is doctrine and sanctification, yet it must also form persons who live inside folk realities—customs, habits, and inherited moral expectations. Augustine’s insight in City of God anchors the axiom: earthly differences endure so long as they do not hinder or contravene piety and morals. And Grentrup ends where ordinary life ends: festivals, habits, the way Christmas fuses religious core with folk custom without destroying either. The picture is neither a pious cosmopolitanism nor a mere folk religion; it is ordered harmony, maintained by doctrine and disciplined by moral truth.

Why This Book Matters (and Where It Can Be Misread)

Grentrup is doing conceptual hygiene. That sounds modest; it isn’t. In an age when modern states and modern myths live by dissolving older loyalties and forbidding nature, anything that restores the grammar of peoplehood—without turning it into paganism—has strategic importance. He gives us a way to speak about folk, boundary, body, continuity, and moral order without falling into either absolute race-myth or administrative deracination. He helps us, first, to rightly think, and then, second, to rightly say “this is real, this is good, and this must be defended” without saying “this is God.”

If the book has a vulnerability, it is the same vulnerability possessed by all restrained works in an age of slogans: it can be used as a “moderate” fig leaf by those who want just enough realism to sound serious while remaining unwilling to draw the practical lines that said realism necessitates. But that is not Grentrup’s fault. His distinctions, honestly applied, do not leave room for managerial erosion or modulation. They also do not leave room for folk-idolatry. That double refusal is exactly why the book is worth keeping close.

For readers concerned with national eudemony, Part One gives a disciplined account of folk life as organic continuity under moral evaluation. Part Two restores transcendence and blocks the temptation to divinize the folk. Part Three shows how Christianity in doctrine and institutions consecrates rather than dissolves distinct peoples, preserving independence while calling all to truth.

It’s a serious work—quiet, sharp, and discriminating.

You can pre-order it now at Sacra Press. Or you can get a free copy upon release with any subscription at Sacra Press through February.